After studying the design of an existing process, I was asked “Why do we need to know the ideal state of the process?” It’s a good question. While there are many good and important reasons to understand the designed capacity of the process, I’d like to consider three points with you today.

Point-1: Deming said “If you can’t describe what you are doing in terms of process, you don’t know what you’re doing.” The process itself exists in layers within the Business Process Architecture. What does that mean? Some might imagine an onion that has concentric circles, some might imagine a diagram of an org-chart that shows different levels of resolution, some might imagine a Quality Management System with its differing forms of written documentation. All these visualizations illustrate that layers exist.

The same concept applies to the process itself. The closer to the work, the more granular the process understanding might need to be. The reverse is also true. The further from the work, the higher the process understanding might actually be. Because of this fact, the practitioner might need to discern at what level of detail is it appropriate to problem solve. Having a clear understanding of the process design enables that discernment which then enables good discussion, collegiate debate, and process-oriented problem solving that is practical and tactical.

Point-2: When it comes to managing the operation, understanding the maximum capacity of the process is important. Without this understanding, the risk is to expect too much from the employees. The unintended consequence might be to work the people harder and not smarter. If an operation understands the maximum output based on the work content time of that process, then it can make better choices related to overall staffing, to cross training, to the use of over-time, to adjusting the capacity of the operation based on ebbs and flows in the volume for the period. It can find the time to do all the work with the same resources. It can shift from “fire fighting mode” to pro-active problem solving and people development. The operation can actually work smarter not harder. There is a science to it. There is a method. Understanding the ideal state for that process is the foundation of the method.

Point-3: Lastly, I will consider briefly the topic of revenue recognition. As you know, in some areas, the practice might be to recognize revenue as the transaction/product moves through the process. What is the science behind deciding how much revenue to recognize and at what points in the process? I submit to you that understanding the design of the process and the work content time for the process in a systematic and methodical manner might help enable discussions related to the practice of revenue recognition and how the business chooses to recognize revenue. While the LEAN practitioner might not be an expert in accounting practices, his practical and tactical skill in process design and development might be helpful in enabling fact-based dialogue related to accounting practices.

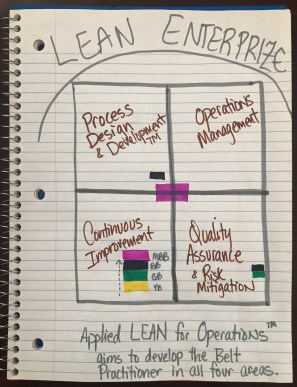

In closing, the reason why a business might need to know the ideal process state and maximum capacity extends beyond the practice of continuous improvement and moves into the business areas of capacity management and accounting practices. All three of these areas (continuous improvement, capacity management, and revenue recognition) has a practical impact on the business.

Takt Time

Takt Time