In the ASQ Global State of Quality 2 Research Report, “Discoveries 2016”, we learned that less than 2% of companies that embark on a Quality journey achieve world-class levels of performance (1). The question is “Why?” While this is a loaded question and cannot be solved in a single blog, what I’d like to do is to begin a dialogue with the community of practice around the subject.

When we look at the practice of Quality over the past 40 years, we see many corporations jumping onto the Lean, Six Sigma, or Lean Six Sigma, or Lean Sigma bandwagon. So, why is it that over this same time period, we see so few corporations achieve world class performance?

I have given some thought to this question.

My observation is that when a company begins its Quality journey (I will refer to this journey as “LEAN” though it might be inclusive of other Quality initiatives) it usually starts with training and certification of belts. These are the practitioners of the trade. Many companies bring in consultants and hire MBBs to get the change language out to the many employees so that they might become practitioners and help the company achieve its goals. Then we know that after the initial few years the momentum lags and the company asks itself “why“. There are many thought leaders in the industry that have sought to understand this problem and have raised the discussion from the toolbox to the mindset, behaviors, and culture. This is very true and necessary. I think, however, that there is more to the conversation, more to the practice, and more technical skill to be developed.

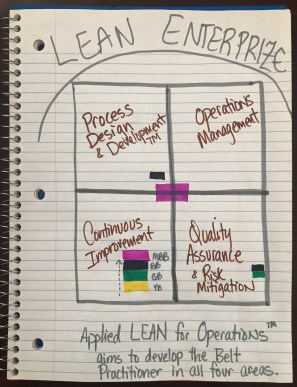

From a practical and tactical standpoint, there is simply more to LEAN practice than continuous process improvement. Over the past 20 years of education and practice, I have come to understand that the application of LEAN really falls under four distinct areas for the practitioner to master. Those areas are in: Process Design and Development (I refer to this as Process Design and Development Methodology TM), the practice of LEAN Operations Management, the practice of Quality Assurance and Risk Mitigation using LEAN/Quality techniques, and the practice of Continuous Improvement (CI).

There is LEAN science behind all four of these areas of practice. My observation is the emphasis in industry, however, is really on culture change and the practice of continuous improvement. Our commonly used belt structure is focused on the CI quadrant with a few tools sprinkled in that are applied in the other quadrants. Upon reflection, I can see why that might be the case from a business standpoint. Usually, when the LEAN journey begins, the thought is to reach many employees and enable them with skill to improve the way the work gets done. Continuous improvement can be practiced without achieving world-class performance, and we know this to be the case for 98% of the companies that try it.

To achieve world-class performance, there is more to the practice than simply improving processes. Processes get designed and developed, processes are managed in an operations within the organization (regardless of the type of operation), processes experience errors and sometimes risks are identified that might need to be mitigated. In all four quadrants, the practice includes practical and tactical techniques based on LEAN Science. I have come to understand this to be called “Applied Lean for Operations (TM).” It is “the art and science of LEAN Sigma practice beyond certification.”

My intention with this blog is to begin a discussion and share with the broader LEAN Community of Practice the technical areas in which we can grow as LEAN practitioners. We have the opportunity to add value to our companies, organizations, and communities with expertise that extends beyond certification.

I hope you will join me in the discussion. Good Cheer,

Azizeh

Blog-1 References:

(1) globalstateofquality.org published research done by APQC and ASQ entitled “The ASQ Global State of Quality 2 Research Report, Discoveries 2016”

Disclaimer: The postings on this site are the author’s and do not necessarily represent the position, strategy, or opinions of UL or any other organization for whom the author has done work presently or in the past. The author reserves the right to change her opinion on these subjects at any time in the future.